I am just old enough to remember card catalogues in research intensive libraries. These were organized on index cards; on the front side was the official typed information. On the back one might find penciled remarks scribbled by librarians and scholars. These would provide helpful information on what one might find at the location printed on the front side of the card. In long established research libraries, one might also wish to consult the old card catalogue that would also have such accumulated wisdom on the back of the card.

My own baby-steps in research, in the mid 1990s, involved a number of cases of locating material that was not in the official card catalogue or of realizing that the front (official) side of the card catalogue did not match the contents of a box or dossier properly. I recall the thrill of adding modest notes to the catalogue with the approval of the head librarian. While scribbling my remarks on the back of the index card, I felt very much part of an immortal republic of letters, literally letters, that crossed boundaries of nation and creed to support our collective enquiry.

I recalled these halcyon days this week in the British Library (or ‘the Mothership’). The Mothership is still hamstrung by an attack by a hacker group last Fall. In particular, the catalogue itself is still hamstrung. If you go to the website you will find the following message:

In addition, you’ll see the following message:

The crucial bit is in the bottom left corner of the screen:

What this doesn’t quite capture is that the Mothership itself is still having trouble locating its own inventory. So each time I have ordered a work manually, it’s not just taken the library a lot more time to retrieve it from storage, but more often than not there has been some kind of error in the process (either my handwriting, a clerical error, or an inventory error).

Now, as regular readers have discerned, I have been drafting a paper on the way Kant and Bentham’s perpetual peace plans are indebted to Smith’s Wealth of Nations (see here). A key bit of evidence for my argument was published in 1839 by Bowring as “A Plan for an Universal and Perpetual Peace.” (A Plan.) This is the fourth essay of a work published as Principles of International Law in Part VIII of The Works of Jeremy Bentham, William Tait Edinburgh, 1839). Somewhat confusingly it’s also sometimes listed as volume 2 of this edition. (Keep that in mind.)

As an aside, if one reads nineteenth century and early twentieth century authors who engage with Bentham and his impact on the ‘radical’ tradition, they usually simply cite Bowring by page-number often obscuring what work of Bentham’s they are citing.

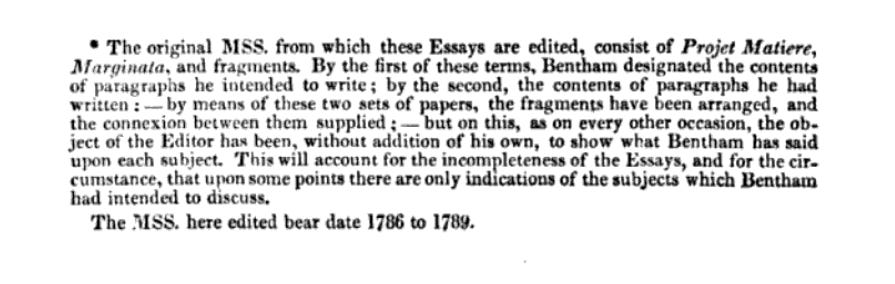

Now, Bowring added a note to his Principles of International Law (on p. 536) that I have reproduced here:

This hints (recall) at some of the textual issues one may be worried about if one decides to write about this material. Modern scholars have discerned that Bowring re-organized the material in all kinds of ways. And the essay he published as A Plan is actually a compilation of three (intended) essays. One scholar, Gunhild Hoogensen (2001), called A Plan a “Frankensteinian” compilation.

Now, because I was puzzled why my (online, google.books) edition of Bowring’s edition of the Works was listed as Part VIII and not Volume 2, I decided to try my luck with the British Library catalogue and try to compare the volumes side by side. Eventually the reference librarian in Humanities 1, directed me back to the Rare Books & Music room.

There the comedy continued because while I managed to look at lots of editions of Bentham, I did not obtain the two I needed. At some point, the very patient even spirited reference librarian asked me the perfectly legitimate question why I didn’t use google.books? I explained my motives to look at a hard copy. He sighed, and called down to the Oriental Institute (in the basement) to see whether my volumes could be tracked down.

As this set of events was unfolding, I noticed in one of my notes the suggestion by Aaron Garrett (BU) to track down Philip Schofield of the Bentham project. I wrote him asking whether there is a modern or critical edition of “A Plan.” I received an incredibly prompt and kind response. Schofield offered me a decade old (unchecked) transcript by Benjamin Bourcier of the manuscripts that are in box 25 of the UCL Bentham Papers. Bourcier had produced it for his PhD in Lille.

After some modest back and forth I obtained a PdF of the transcript with permission to use it as long as I acknowledged doing so. Unfortunately, Schofield added the warning that the accuracy of the transcript could not be guaranteed. I suddenly realized I was turning into a character of an Umberto Eco novel planning to compare a Frankensteinian compilation with a transcript of uncertain quality.

I pointedly ignored Schofield’s very generous offer to send me pictures of the manuscript. In my draft paper, I had already screened off any claims about Bentham’s intentions—these could not be established without a more secure edition. I was using A Plan to say something about Bentham’s engagement with Smith and how this could have been received by readers of Bowring’s edition. I was not planning to aid in Benthamite textual philology.

Now, as I was comparing my quotes from Bowring (on Google) with Bourcier’s transcript, a thought occurred to me. The reason why I was so confident linking A Plan to Bentham’s reading of Smith was that the manuscripts Bowring has used date from the late 1780s. Bentham’s Defense of Usury dates from 1787, and this shows non-trivial command over Wealth of Nations. So, despite the fact that A Plan makes no mention of Smith (and is presented by Bowring as a response to Tucker — recall that — and Anderson), I assumed nineteenth century liberals and radicals would have recognized the Smithian themes in it. What if I searched for references to Smith in Bourcier?

One of the manuscripts is titled, ‘Internat. Protest.’ Bourcier lists it as 025-112. (It’s about four pages in his transcription.) The material is not in A Plan (as can also be inferred from Hoogensen 2001), and a relatively quick spot check suggests Bowring didn't use any of it it anywhere in Principles of International Law. I quote it with permission:

This is my creed.

Did it depend on me I would not obtain for my own nation the smallest privilege of which I would not impart in equal measure to every other nation. Did it depend on me I would not obtain for myself the smallest privilege in which every fellow-citizen according to the measure of his natural faculties, was not an equal sharer with me. Equality is Equity: and Equity is the only wisdom and where there is no equity surely there is no wisdom.

If a system of common sense and common honesty is to begin any where, where should it begin, but with us? Who can begin with most safety. Who with most dignity? Who can have less to fear from it? Who else but we could venture to begin it. If glory by being purified from wickedness and folly does not lose its value, the parcel glory that can be attained by any nation, the brightest glory that can be obtained by man is most peculiarly our own.

In much of this to speak form vague and general recollection, I have been forestalled by Dr Tucker: in other parts by Dr Smith. Alas! I wish I could say superseded! Such is the progress of human wisdom. Discovery comes in one age, demonstration in a second: conviction in a third reformation if ever in a fourth. The men who err are scarce ever the men who reform: and reformation will scarcely come unless handed in by spite…

It’s not my smoking gun. (It can’t be because its connection to A Plan is so opaque.) Yet, it’s even better than that; I repeat I would not obtain for my own nation the smallest privilege of which I would not impart in equal measure to every other nation.

In the Rare Books room I hold the paper order form for Bowring’s Works like a lottery ticket. A huge wave of gratitude sweeps over me toward Benjamin Bourcier and the ethos that sustains disinterested scholarship of archive-rats in an uncaring universe.

Sometimes, chance favours the well-prepared. Ask me sometime about my accidental goldfind in 𝑆𝑜𝑐𝑖𝑒́𝑡𝑒́ 𝐿𝑖𝑛𝑛𝑒́𝑒𝑛𝑛𝑒 𝑑𝑒 𝐵𝑜𝑟𝑑𝑒𝑎𝑢𝑥.