Last week my paper with Nick Cowen and Aris Trantidis, "Democracy as a competitive discovery process," was published online (and open access) in European Journal of Political Economy. I have discussed the paper before so won’t repeat that now.

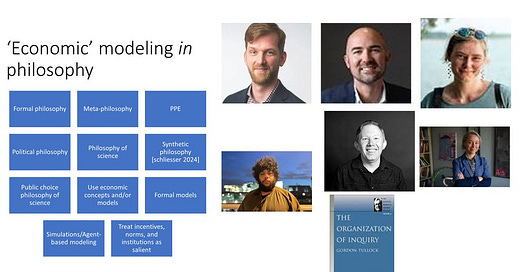

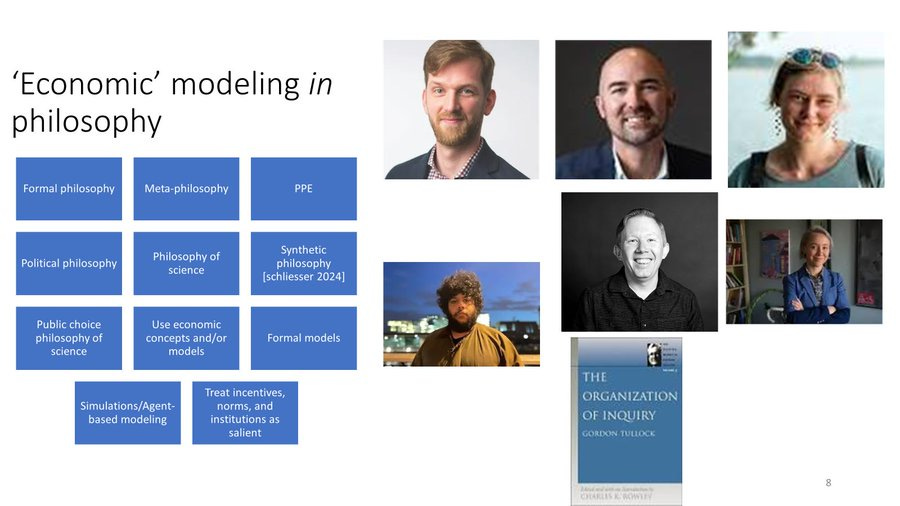

Yesterday, in order to self-advertise, an invited presentation “Some (Marxist and Liberal) Pre-History to Philosophy as Economic Modeling,” in Salzburg on Friday (see here for info—thank Julien Murzi), I shared a slide from the lecture on Facebook. For reasons that are left unclear to me (‘community violation’), I was immediately banned from Facebook. I have appealed, but welcome to arbitrary governance. Anyway, I re-share the offending slide here. I am a big fan of the people on the slide, so I could be banned for a lot worse reasons.

Today’s post is on a somber topic (and brief). It was triggered by an invite from Diana Popescu (Nottingham) to present later this month at the CRISPI Conference June 2025: The Idea of Freedom and Modern Slavery (here). I love invites that nudge me into expanding my intellectual horizons!

For various reasons I have gotten fascinated by the work the idea of ‘modern’/‘modernity’ does in contemporary philosophy (and political life more generally). So, my paper will be about the rise of the very concept ‘modern slavery.’ As regular readers know I suspect this originates (recall) in a late nineteenth century liberal critique of imperialism by (benevolent racist, alas) classicists; these liberals were familiar with Aristotle and Marx, and needed a term to discuss non-chattel, but forced industrial labor that instrumentalizes the people so used. More on that next week.

But a mild unease sent me back to Thoughts and sentiments on the evil and wicked traffic of the slavery: and commerce of the human species, humbly submitted to the inhabitants of Great-Britain (1787) by Ottobah Cugoano, which I teach annually. As it happens he uses ‘modern’ six times in the work. And each time it is conjoined with (you guessed it) ‘slavery.’

Now, when Cugoano refers to ‘modern slavery,’ he means the slavery practiced on kidnapped ‘black Africans’ (p. 43) in the Carribean sugar islands (e.g., p. 40) by purported ‘Christians’ (p. 64). In addition to ‘modern’ he usually conjoins some version of ‘cruel’ (p. 18; p. 40; p. 43; p. 58) and barbarous’ (p. 40; p. 43) with it.

In fact, we can really discern two reasons for Cugoano’s emphasis on the ‘modern’ nature of modern slavery. First, it is practiced by people who pride themselves on being more advanced than ancient barbarians (pp. 39-40 & p. 58). Cugoano explicitly includes the ancient Romans and Greeks among these barbarians (p. 58). But in their contemporary dehumanizing practices (pp. 17-18) the Europeans reveal themselves as more barbarian than the pagan barbarians. Here Cuguano echoes the rhetorical strategy of Enlightenment reformers of the criminal justice system (Beccaria, André Morellet, Voltaire, and anticipating Grouchy), who would routinely point out that the purported civilized Europeans revealed themselves as more barbarian in their torture than purported barbarians.

Second, he wants to show that the modern institution of slavery knowingly violates the biblical injunction against kidnapping innocent people into slavery. (p. 64; Cuguano does not, in fact, reject all slavery; but about that some other time more.) So, qua Christians, these modern slavers are the worst kind of Christians.

Below the passages that I have relied on:

But thus saith the law of God: If a man be found stealing any of his neighbours, or he that stealeth a man (let him be who he will) and selleth him, or that maketh merchandize of him, or if he be found in his hand, then that thief shall die. However, in all modern slavery among Christians, who ought to know this law, they have not had any regard to it. (p. 64; emphasis in original)