Helena Rosenblatt's Lost History of Liberalism, Liberal Perfectionism, and a statue outside Mornington Crescent tube station.

Anyone (novice and expert) interested in the long history of the use of ‘liberal’ will enjoy reading and learning from Helena Rosenblatt’s (2018) The Lost History of Liberalism: From Ancient Rome to Twenty-First Century. It is especially fascinating on the French nineteenth century debates over Church vs State in general,* and the role of education in these in particular. It centers Constant and De Staël, and so is a useful corrective to twentieth century liberal hagiography of Locke. Unlike many histories of liberalism, it also devotes considerable attention to the role of ‘liberal’ in theology and religious reform. And while it is not hostile toward liberal self-understanding it does not ignore to mention liberal enmeshment in empire, race science, eugenics, and anti-feminism when it occurred.

In her account liberalism is both a contested term with a great variety of uses (here she echoes Duncan Bell’s (2014) “What is Liberalism?,” and (simultaneously) owes its origins to the “French revolution” (p. 5 & p. 246). I have disagreed with this claim (recall here; or here), and won’t relitigate that. Crucially, for Rosenblatt “wherever it migrated thereafter, it remained closely linked to and affected by political developments in France.” (p. 5) She centers her narrative on the revolutions of 1789, 1930, 1848, 1870 and their impact on “transatlantic debates” (p. 6).

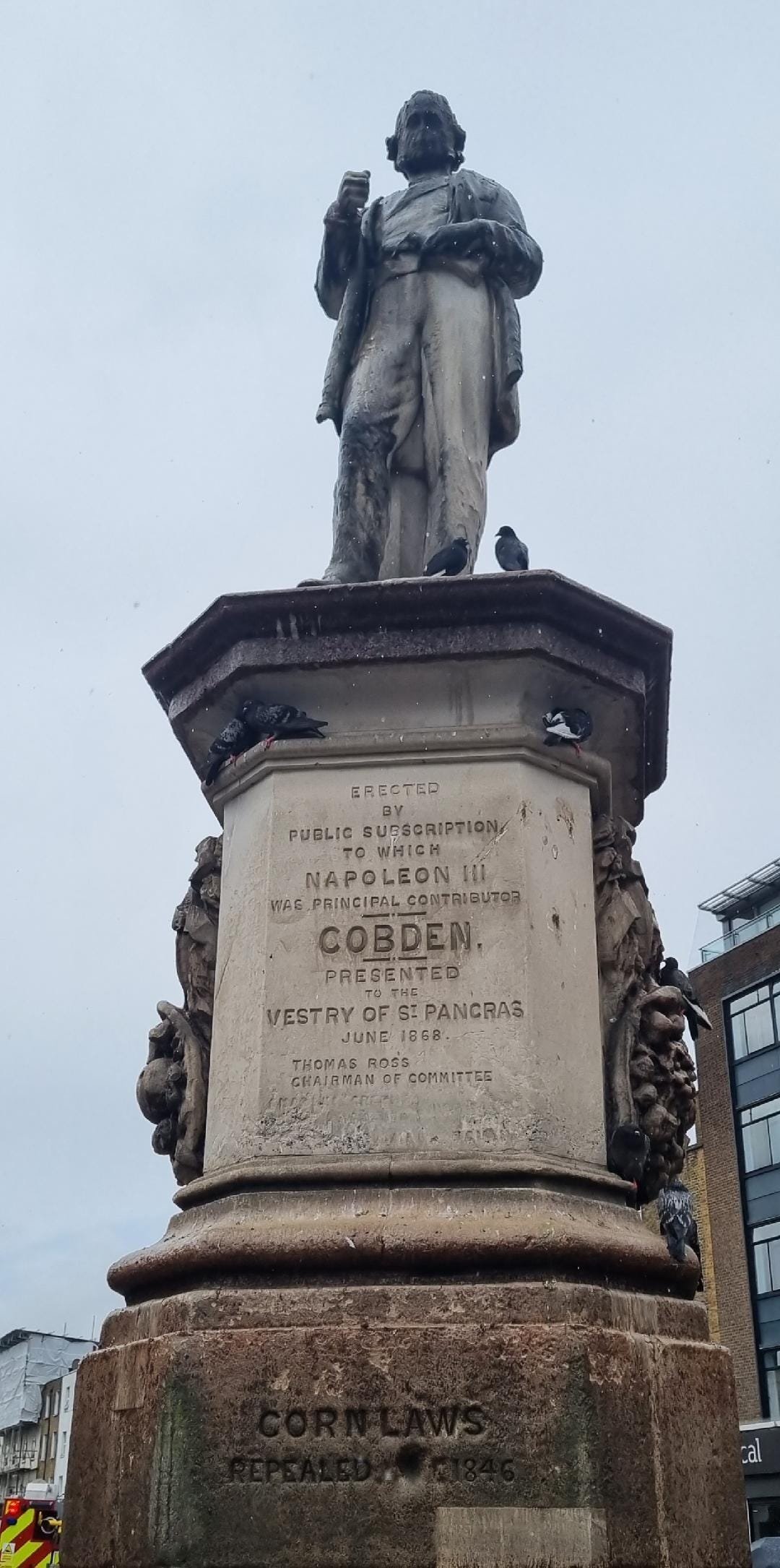

Even so, I think even for the French case something goes awry in her account. And to begin to see why we should take a look at a picture of a statue in front of the Mornington Crescent tube station, Camden (see below). It’s a statue of Richard Cobden (b. 1804), erected in 1868, three years after Cobden’s death. (The tube station came later, by the way.) There is no obvious reason why the statue was erected there. As the statue reminds passersby Cobden helped repeal the corn laws. But why would (that usurper) Napoleon III contribute to commemorate him?

If we go to Rosenblatt’s book (which has quite a bit to say about Napoleon III), the mystery deepens. Here’s the sole mention of Cobden:

Such thinking [viz, criticism of French invasion and conquest of Algerian] aligned French critics of colonialism with British free traders like Richard Cobden and John Bright, leaders of the Anti-Corn Law League. They too denounced an empire based on violent conquest that served the interests of only a small minority of the population. In Bright’s famous words, the empire was “a gigantic system of out- door relief for the aristocracy.”—p. 115

Most critics of Manchester-liberalism don’t mention his critique of imperial conquest, so I don’t think Rosenblatt has any particular animus against Cobden or Bright—she is just not very interested. Rosenblatt omits mention of Cobden and Bright’s courageous criticism of the Crimean war and their more general advocacy of a policy of non-interventionism.** When she lists the liberals who supported the North during the US civil war she does not include them (which is a shame because Bright’s speech at Rochdale, December 4, 1861, is one of the greatest bits of liberal oratory of all time). As careful readers will note, Rosenblatt implies that Cobden and Bright may be more sanguine about pacific empire. (I return to this below.)

There is a simple explanation of Napoleon III’s contribution to the statue in Cobden’s memory. Cobden negotiated the so-called Cobden–Chevalier Treaty of 1860 between France (then ruled by Napoleon III) and Great Britain. The significance of this treaty is not so much that it abolished restrictions on major areas of trade, but rather that it also included what we now call a “most favoured nation” (MFN) clause that stipulated that if you grant some country and its citizens MFN status by treaty, then any rights or privileges you give to other countries and its citizens (in other treaties) automatically accrue to the MFN country and its citizens.

To be sure, it was not the first such clause in a trade treaty. In the 18th century, Molesworth describes such a clause in a treaty between Denmark and the Hanseatic cities in 1692, when he was ambassador in Denmark (see here). But, inspired by Bentham’s argument published in 1843 as “A Plan for an Universal and Perpetual Peace” (recall here), in Cobden’s hands free trade and MFN were part of a wider set of functional mechanisms (including arbitration) that were supposed to shape pacific relations among states, including as a mechanism toward federalism.

Now, Rosenblatt regularly mentions free trade, and she quite rightly emphasizes that liberals disagreed about its nature. But because she is so focused on liberalism’s role in French domestic and constitutional politics, she largely misses the liberal advocacy of federalism even world government since Smith, Kant, and Bentham. This is especially odd because President Wilson plays a pivotal role in the concluding parts of her argument (234-247), and yet somehow the League of Nations goes unmentioned. Wilson’s emphasis on open diplomacy could be cribbed straight out of Bentham.

Today I want to mention two more related peculiarities (and leave other criticisms aside) in her narrative. To her credit she devotes attention to British liberal socialism or “new liberalism” paying particular attention to T.H. Green, Hobhouse, and J.A. Hobson (see, especially, pp. 23-235). I start with an hominem argument. She treats Hobson as “one of the most original political theorists of the time” and quotes him as starkly announcing that “the old laissez-faire liberalism is dead.” (p. 230)

Rosenblatt implies that British left liberalism was primarily shaped by Bismarkian “German ideas” on welfare as well as the “ethical economists” by which she means, especially Roscher, Bruno Hildebrand, and Karl Knies (pp. 220-225). This is an important point. Yet, somewhat oddly there is no mention of Kant’s or Hegel’s impact on Green, in particular.

But while important, it also misleading. For example, Hobson was also a huge admirer of Cobden. In fact, I first learned most of the material I have discussed above from Hobson’s admiring (1919) Richard Cobden - The International Man. Hobson’s famous work on Imperialism is shaped by Smith’s political economy not the German ethical economists.

In fact, Hobson and Hobhouse presented themselves as the true heirs of Cobden. While Mises barely mentions Cobden in his (1927) work Liberalism, Hobhouse treats Cobden rather seriously in his (1911) Liberalism. (This work partially supports Rosenblatt’s emphasis on the French revolution by the way, but completely ignores Constant.) At first it seems Hobhouse presents Cobden as a laissez-faire thinker (combining Smith and Bentham). I certainly don’t mean to deny that Hobhouse is critical of Cobden’s account of freedom, especially.

However, as he develops his case he makes the following observation on Cobden’s criticism of war and imperialism:

The money retrenched from wasteful military expenditure need notall be remitted to the taxpayer. A fraction of it devoted to education—free, secular, and universal—would do as much good as when spent on guns and ships it did harm. For education was necessary to raise the standard of intelligence, and provide the substantial equality of opportunity at the start without which the mass of men could not make use of the freedom given by the removal of legislative restrictions. There were here elements of a more constructive view for which Cobden and his friends have not always received sufficient credit. (p. 81 in 1945 reprint; see also p. 36)

Given how important liberal views on education are to Rosenblatt’s general argument this is non-trivial. Cobden is presented as key to the argument from equality of opportunity which Hobhouse himself proudly generalizes.

Okay, I should stop here. But I want to close with a final observation or diagnosis. Rosenblatt’s Lost History is polemically organized, quite rightly, against the idea that liberals were somehow rights obsessed and against the cultivation of virtue (see, especially, p. 274). She is right to recover the centrality of what philosophers call ‘perfectionism’ to the liberal self-understanding. (I happen to think it is also a mistake to conflate and mix liberalism and republicanism as systematically as she does. But, soit! )

But in her treatment, she ends up implying that the laissez-fare liberals were not concerned with virtue or Bildung. This is especially notable in her treatment of Frédéric Bastiat. I am myself not especially enamored of Bastiat, but it is notable that she only calls him an “ideologist.” Yet, while there is undoubtedly some victim blaming in Bastiat, he thinks bad government policy (and incentives) is the true source of social misery.

Now, there is no doubt that Bastiat is quite critical of governments imposing their idea of virtue on citizens. But that’s not because he is critical of virtue as an (indirect) aim of policy. Rather, he thinks, as Rosenblatt notes (p. 145) that in practice when governments aim for virtue, they will end up promoting vice. But that’s not because he is an a-moralist. Bastiat is explicitly what the philosophers call a perfectionist, but of an indirect kind. This is very clear in his Harmonies of Political Economy. In which he argues, for example, that “since the inexorable necessities of material life are an obstacle to moral and intellectual development, it follows that more virtue will be found in the more affluent nations and classes.” (emphasis added). Whether this is true is different matter, but his defense of laissez-fare is offered in terms of the axiom that “Man is perfectible.”

*Having said that, Catholicism and Democracy (2012) by the late Emile Perreau-Saussine is still indispensable further context.

**On this see Hobhouse (1911 [1945]) Liberalism, p. 104.