Back in 1966 J. E. (‘Ted’) McGuire and P. M. Rattansi published a classic paper, “Newton and the 'Pipes of Pan,'” in (here) Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. It partially reproduced and analyzed a number of “draft Scholia to Propositions IV to IX of Book III of the Principia.” These drafts “were composed in the I690's, as part of an unimplemented plan for a second edition” (to be edited by Gregory). A second edition of Principia was eventually published with a different editor (Cotes) but without much of the material in these draft Scholia.

These unpublished 1690s scholia became known as the ‘classical scholia.’ According to McGuire and Rattansi the classical scholia represent Newton’s wish, like Cudworth, to confute 'Hobbists', Deists, and 'hylozoistick atheists.’ As my regular readers know I think Spinoza and Spinozism is very much Newton’s target in the second edition of the Principia (see this book).

A key draft, which gives their paper its title is the following passage:

These are passive laws and to affirm that there are no others is to speak against experience. For we find in ourselves a power of moving our bodies by our thought. Life and will are active principles by which we move our bodies and thence arise other laws of motion unknown to us.

If the passage is discussed at all it is about its role in the argument to what degree Newton thought the cause of gravity is God. (In wider context that is not completely silly.) Either way, here nature does nothing in vain is clearly connected to Newton’s endorsement of general/providential final causes (all things are framed with perfect art and wisdom) and nature’s ordered-ness/law-governed-ness.

As regular readers know, I am rather interested in the principle that nature does nothing in vain in Newton and Spinoza. I am especially struck by Newton’s embrace of it in the 1690s because Spinoza (1677) had been such a critic of it (see Ethics 1, appendix). Spinoza associates the principle with a superstitious expectation of special providence by an anthropomorphic God. Recall this series of digressions (recall; and here; and here.)

When Newton did re-draft what came to be the second edition of the Principia, he changed the hypotheses at the start of Book III into Rules of Reasoning. That’s incredibly well known. But today I noticed a fun detail. Here’s the first edition of the Principia:

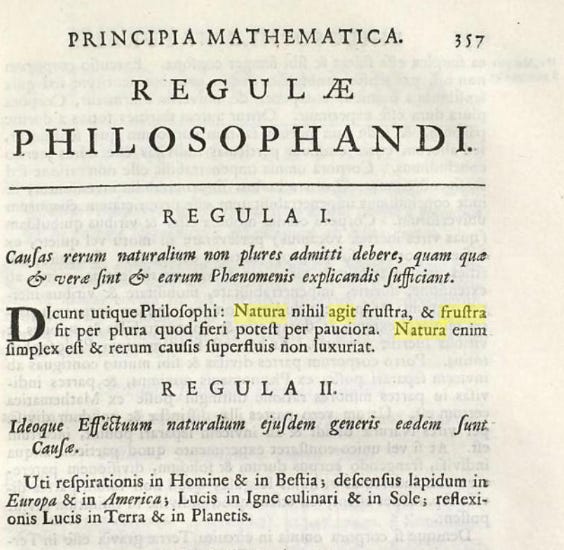

Now here’s the second edition. So, as expected Hypotheses have been changed to rules. But in addition, Newton has added a further claim:

To follow Janiak’s translation: “As the philosophers say: Nature does nothing in vain, and more causes are in vain when fewer suffice.”

So, to the best of my knowledge the addition of ‘nature does nothing in vain’ to the second edition has not elicited any commentary! I am very excited about this. Feel free to alert me to evidence to the contrary.

What’s especially odd is that ‘nature does nothing in vain’ is introduced by way of the authority of the philosophers and that Newton does not require the principle for the point he is making. He could have just stuck with an appeal to nature’s simplicity as a justification for his first rule of reasoning.

Another reason why it’s odd is that the rules of reasoning, and especially the first two, are about causal ascription of what the Aristotelians would have called efficient causes (that is, forces as the sources of accelerations). But ‘nature does nothing in vain’ is not just an appeal to ordered-ness, but would have evoked some link to final causes to contemporary readers. And this link is never made explicit by Newton until the General Scholium at the end (also added in the second edition), where Newton defends the existence of the most general final cause, God.

In fact, the material in the previous paragraph is connected to another important change Newton made to the body of the Principia (a point I have dwelled on before): the only explicit mention of God in the whole first edition of the Principia was removed from the body of Book III: ''Therefore God placed the planet at different distances from the sun so that each one might, according to the degree of density, enjoy a greater or smaller amount of heat from the sun'' (Book 3, proposition 8, corollary 5; p. 814). This claim, which presupposes God’s providential order, was dropped altogether in subsequent editions. (Interestingly Huygens, Kant, and Adam Smith were familiar with it.) And Newton moved his implied natural theology -- without this particular argument -- to the new conclusion of the Principia, his anti-Spinozistic General Scholium.

This is all I wanted to digress on. Obviously, it would help my case immensely if I could show that Newton was familiar with the fact that Spinoza treated nature does nothing in vain with scorn. To be sure, in Newton’s circle it was very well known that Spinoza was a critic of final causes. (That’s a major theme of Henry More and Samuel Clarke’s criticisms of Spinoza.) So, it could be inferred. But it would be nice to find documentary evidence.