I wanted to write a post on how President Biden’s full employment strategy has backfired. Early in the Summer publications (like Slate) could write, that he “restored full employment as the bedrock economic commitment of the Democratic Party.” (This was written by Zachary D. Carter, the author of a work on Keynes.) And, in fact, “Even accounting for inflation, Americans today have more money in the bank than they did in 2019, while wage and income inequality have declined.” For most of October, I thought tomorrow’s election would suggest that the electorate would resoundingly say, ‘no thank you’ and lead to a potentially catastrophic defeat, fairly or not, of Vice-President Harris. (After the election I will do a post on foreign policy.)

And the reason for this defeat would be that the benefits of full employment tend to be relatively concentrated, but the costs (inflation) widely dispersed. And so we would not see a renewed experiment with it for another generation or two. After all, the experience of high inflation seems to have driven a non-trivial part of the electorate to express higher trust in Donald Trump (a man intrinsically untrustworthy) on the economy (despite proposing policies that will undoubtedly be inflationary).

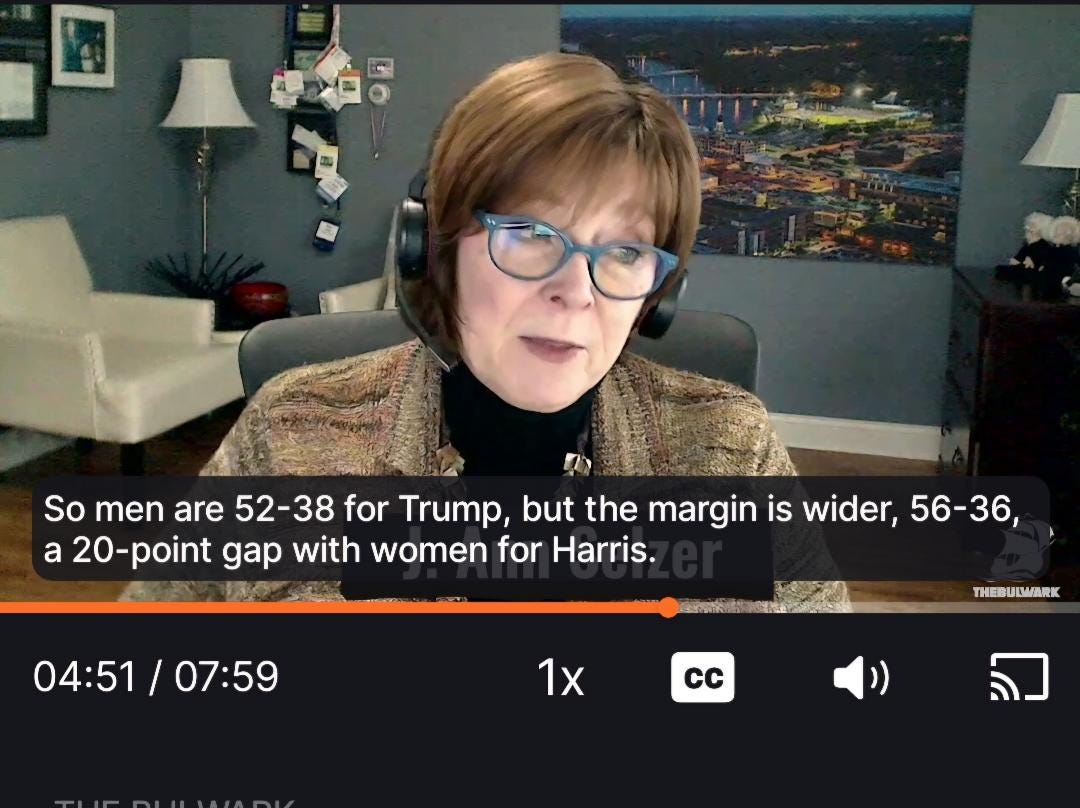

Then, about two weeks ago, I started to notice reports like this:

Now, among political junkies it’s also well known that “Women are registered to vote in the U.S. at higher rates than men. In recent years, the number of women registered to vote in the U.S. has typically been about 10 million more than the number of men registered to vote. However, that gap declined to 7.4 million in 2022.” In addition, “In every presidential election since 1980, the proportion of eligible female adults who voted has exceeded the proportion of eligible male adults who voted.” (And within this group, older and educated women are also disproportionally represented.) Thus, the general gender gap that is showing up in the polls ought to predict a landslide Harris win (as I noted on social media (here) on October 26). Some of the social media comments by Lily Mason (Hopkins) had got me thinking about this.

So, I had been puzzled by all these remarkably close state polls in so-called ‘swing states.’ Either that extreme gender gap doesn’t exist or something distinctive is happening in swing states. I had, thus, been actually somewhat relieved to see that many expert (like Nate Silver) insiders are considering an alternative explanation: herding by pollsters. We should be seeing much more variance in the polls.

As an aside, if Silver is right about the reality of herding it does raise interesting questions about how one should update. (Silver is a prominent Bayesian.) Bayesianism doesn’t secure one against the risks captured by the slogan of ‘garbage in, garbage out.’

However, after moment’s reflection I realized that this (herding) needn’t be the only explanation of the lack of variance because many pollsters are, as Nate Cohn has explained, using weighted samples to account for so-called shy Trump voters. In particular, they are assuming that the electorate this year is much like the electorate in 2020. And if you use weighted samples, you may expect much less wide distributions. (For a nice explanation see Justin Wolfers’ thread here.) But when you weight like that it also means you may be preventing yourself from picking up a signal in your data.

As you may have heard, Ann Selzer published her final Iowa poll sponsored by the Des Moines Register (here) over the weekend; this poll shows Harris up by three among likely voters in Iowa. In an interview she did (here) at The Bulwark, she explained her finding. A key bit of the explanation (see the image below) is — you guessed it — that gender gap. In particular, independent (and older) women are breaking for Harris (something she emphasizes in her BBC interview here). She herself thinks this is a consequence of the topicality of abortion bans in Iowa.

Interestingly enough, if you listen to the fine-grained details of Selzer’s argument she doesn’t think the electorate is exactly the same as in 2020. It has also widened with new voters.*

Even if Selzer’s finding is true for Iowa it need not translate nationally or (despite closer demographics) regionally. Most of the abortion bans after Dobbs (2022) were in the South. However, Missouri and Nebraska also banned and so they may be more in ‘play’ than recognized.

I am just old enough to remember when Iowa was a swing state with a robust progressive strain. (Obama won there.) I briefly volunteered for Senator Harkin’s presidential campaign more than thirty years ago. The national campaigns have not spent money or time in Iowa this year around.

Lurking here is more general observation that since the implosion of the Reagan-Gingrich-Bush coalition, the Republican party has transformed and thereby attracting new voters, especially those focused on immigration. (Most dramatically in Florida and Ohio formerly swing states.) It has also quite clearly nudged out educated, suburban voters by frequently signaling reservations about science and expertise during the pandemic.

To put the point more abstractly: since 2016, the coalitions are re-aligning in part driven by wider demographic trends, and in part because the two parties really have developed very distinct political outlooks. So, American voters really are offered a genuine and intense political choice between the two parties along many dimensions. (Not all dimensions worth having, of course, but that’s inevitable in a two-party system.) Unsurprisingly, in the context of this polarization, the last few Presidential elections turn-out has sky-rocketed relative to the last century (but not compared to other countries.)

However, as coalitions re-align in terms of values and interests, they also enact policies and win political victories that may also cause further realignments. This is a mechanism that Montesquieu captured in somewhat deflationary fashion in The Spirit of the Laws. I quote (recall) Book XIX, chapter 27 (“How the Laws contribute to form the Manners, Customs, and Character, of a Nation”) in which Montesquieu first presupposes intense polarization. He then notes a subsequent effect that he puts in rather deflationary fashion:

As these parties are made up of free men, if one party gained too much, the effect of liberty would be to lower it while the citizens would come and raise the other party like hands rescuing the body.

As each individual, always independent, would largely follow his own caprices and his fantasies, he would often change parties; he would abandon one and leave all his friends in order to bind himself to another in which he would find all his enemies; and often, in this nation, he could forget both the laws of friendship and those of hatred. [emphasis added.] Translated by Anne M. Cohler (et. al).

Dobbs was a huge victory for a faction in the Republican party coalition. But it also clearly went much further than many ordinary Republicans wished. So, if the polls are finding a real gender gap, then even leaving aside the effects of Trump’s character, the Dobbs ruling has accelerated the movement towards the Democrats among older and educated women. It has also, somewhat unexpectedly, allowed national republicans to soften their platform on abortion (which has generated non-trivial discussion among religious conservatives). How much this will matter we will find out soon. I don’t know. Perhaps, Iowa farmers are also not so keen on trade-wars with China and tariffs.

But lurking here is a more important point. Montesquieu’s observation, written by reflecting on an idealized account (by Bolingbroke) of the British constitution of the early eighteenth century, which was very far from a full franchise, is nevertheless important. Electorates are never fully static and even modest movement with a coalition can cascade into fundamental power switches. Being Red or Blue is not an intrinsic quality of an electorate. And so while the focus on swing states as fixed is entirely intelligible, as Montesquieu foresaw each election is also a discovery process of finding out which state may swing next and how to constitute coalitions and even a national representation. (About that, more soon.)

I could have ended here, but some of you may be thinking I am ignoring the elephant [pun intended] in the room. One of the dimensions the parties seem to differ on is a willingness to play by democratic rules. Many people seem to believe that a Trump victory this time around will generate an irreversable process known as ‘democratic backsliding.’ And since the republican party has taken on characteristics of a cult of personality, the guardrails are melting in front of our eyes. (Notice that the Democratic party’s ejection of Biden — a sitting President — as candidate is wholly unthinkable among Republicans right now.)

I dislike that terminology of ‘democratic backsliding,’ because while I am a (skeptical) liberal and a partisan for liberal democracy, I hold that illiberal programs and people can be quite democratic in the majoritarian and Bonapartist senses (amongst others). I also happen to have argued that it is healthy for liberals to engage non-liberals respectfully but critically as rivals. After all, for Liberals free trade and abortion are not just two distinct policy domains, they both involve liberty.

During the last nine years I have never underestimated Donald Trump’s capacity for malice. Even so, I tend to think of him as mostly interested in self-enrichment and aesthetic projects (of which I disapprove). Until the events of January 6, I thought the tendency to treat him as a danger to democracy as such — with well-known Obama and Clinton staffers representing themselves as ‘the resistance’ — a form of play; if you really believed he was a would-be-tyrant, you would be hiding and be a lot more cautious.

Now, I am less sure. Again, even leaving aside his character and his own plans, his program to which people are rallying will involve a great expansion of the state’s capacity to engage in daily harm against suspected undocumented aliens and tariff smugglers. This will predictably accelerate the militarization and expansion of the US border into the heartland (a topic I have been alerted to by Jacob T. Levy back in the day), and empower lots of petty mandarins just as abortion control has turned hospitals into an extension of the carceral state.

Liberal democracy places great faith in the (aggregate) judgments of ordinary people, who in their daily trades, associations, collaborations, and inventions help constitute a new world with unknown destination. Montesquieu suggests that this is also a hidden safety valve because people will defect from the status quo for all kinds of reasons.

Yet, counting on this safety valve also betrays a kind of providential faith that one has the opportunity to do so. Absent the security that providence provides, this means that the ship of state can sail into very dangerous territories every election in which the people decide. Such danger is intrinsic to liberal democratic life, perhaps to any life worth living.

May we be blessed by good fortune.

*Selzer doesn’t use weighted sampling, but a close cousin, so-called stratified sampling.

"if you really believed he was a would-be-tyrant, you would be hiding and be a lot more cautious."

Looking at the record of dictators who might be considered comparable, the risks for moderately prominent opponents, like Democratic staffers, aren't great, assuming they stay reasonably quiet once the dictatorship is established. I expect political prosecutions of people on whom Trump wants personal revenge (the Bidens and Clintons, and even more, the perceived traitors from his first administration). But as you say, the real force will be directed against people whose crime is not political activity but being in the wrong category (undocumented, trans, pregnant etc).