“You have formed into a regular and consistent system one of the most intricate and important parts of political science, and if the English be capable of extending their ideas beyond the narrow and illiberal arrangements introduced by the mercantile supporters of Revolution principles, and countenanced by Locke and some of their favourite writers, I should think your Book will occasion a total change in several important articles both in police and finance.” ---William Robertson, letter to Adam Smith of 8 April 1776, Smith’s Correspondence, p. 192

Not unlike Daniel B. Klein (GMU), I like quoting Robertson’s letter to Adam Smith because it’s one of the earliest reactions to Wealth of Nations (WN) and it shows an informed reader picking up on the fact that ‘liberal’ and ‘mercantile’ are treated as contraries in it. This fact is not advertised, and only apparent from reading Book IV of WN. Of course, Robertson himself was fond of this use of ‘liberal’ (arguably he coined it a a few years before), so he may well have been quite pleased to discern Smith’s emulation of him. In addition, it’s kind of neat (if you agree with my program) to see that at the coining or the invention of ‘liberal’ and ‘liberalism’ in the modern sense Locke is treated as the target and not the founder.

I also like quoting the passage because it shows that the immediate, contextual reception of WN also involves its contribution to political science and politics. In particular, what Robertson discerns is that Smith is critical of a whole ideological and intellectual framework associated with the 1688 Settlement, and of which Robertson treats Locke as a kind of important representative/spokesperson. (As I have noted before, drawing on my colleague Paul Raekstad, Smith kind of invents ideology critique here.)

As I have noted before (here) there are some puzzles lurking here. Smith doesn’t mention Locke so much, so it’s worth reconstructing Smith’s writings such that Robertson’s interpretation seems evident. It’s also not wholly obvious how Smith’s reconstruction of mercantilism makes contact with Locke’s texts. Even leaving aside Locke’s own views, would it have made sense to treat him as the paradigmatic mercantilist qua ‘political scientist’ of the age.

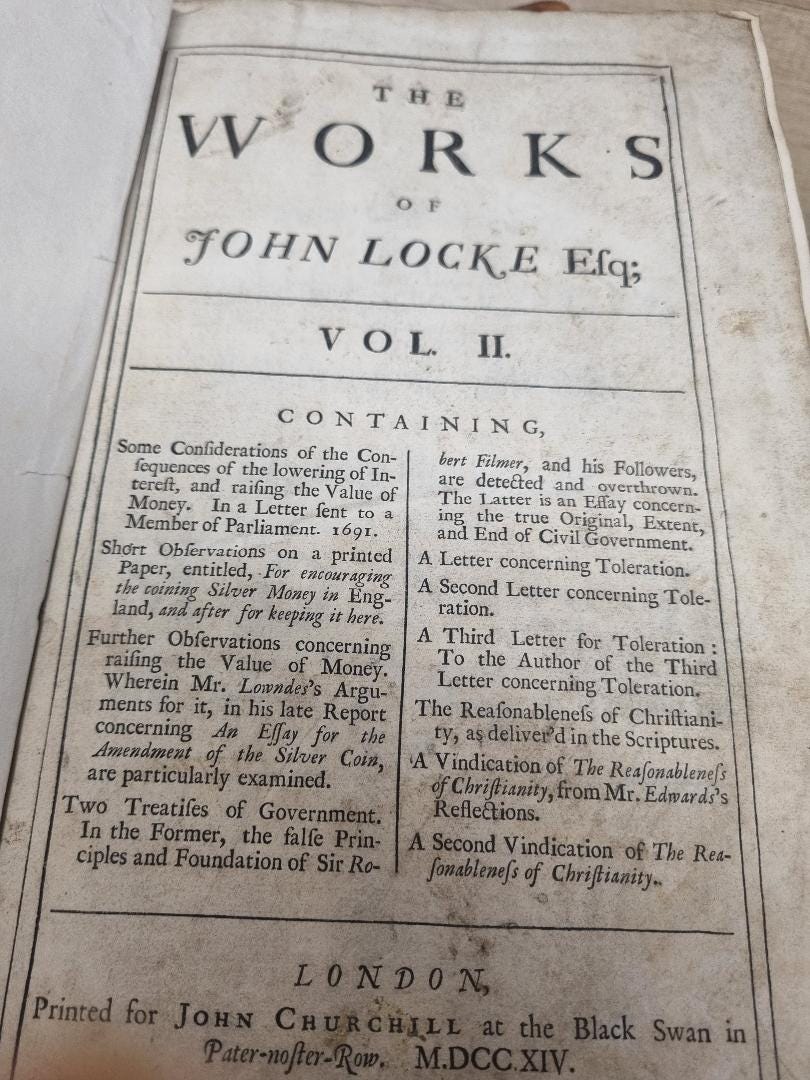

In particular, it’s not immediately obvious why The Second Treatise would be a mercantile work. Part of the problem here is that not everyone reads the same edition of that work. And the moment one reflects on that point, one is pulled into a swarm of controversy related to the composition of Locke’s works and also the relationship among the editions he published during his life, and the definitive text that was published, posthumously, as a fourth edition and then in The Works of John Locke. In addition, there is a trickiness that the non-trivial for political theorists and historians French reception was shaped by a French translation that left out some material. (This is a rare instance where Wikipedia only gives a hint of the controversy).

For example, a key passage was added (almost as a digression) to the posthumously published version par. 42 of the Second Treatise:

This shews how much numbers of men are to be preferred to largeness of dominions; and that the increase of lands, and the right employing of them, is the great art of government: and that prince, who shall be so wise and godlike, as by established laws of liberty to secure protection and encouragement to the honest industry of mankind, against the oppression of power and narrowness of party, will quickly be too hard for his neighbours: but this by the by.

What’s absolutely crucial about this passage is that economic and political considerations are intertwined for Locke. The question is how: At first glance, this passage suggests that the art of government should favor population growth over territorial expansion, and that he way to promote this is through economic growth built on a political framework that facilitates hard work (that is, judicious protection of property rights, low taxes, political freedoms, etc.). There is some controversy over this passage because it would seem to be more natural if Locke’s ‘lands’ were ‘hands.’ (Now it feels as if he is sending mixed messages in the quoted paragraph.)

Now, recently I got a chance to look at The Works of John Locke, which was published by Locke’s publisher, John Churchill, in three volumes in 1714. This edition was the Locke familiar to eighteenth century British thinkers. (This version has ‘lands.’) Crucially, it confirmed his authorship of the Two treatises and the Letter(s) concerning toleration. This edition is in Glasgow University’s library, but I need to check when they acquired it and if it has Smith’s marginalia.*

Now, if you look at the table of contents, volume 2 is structured like an ascent from earthly material stuff toward (the political organization of) our spiritual lives. But, in particular, the connection between Locke’s monetary principles and political philosophy invites reflection.

Now in Some Considerations, it’s pretty clear that Locke actually tends to think of trade as non-zero sum. And this is a view that Locke’s account of property also emphasizes in (the chapter on property of the) Second Treatise. So, this is why libertarians tend to think of Locke as a liberal (alongside his apparently robust defense of property rights).

Eric Mack (Tulane) has recently usefully looked at Some Considerations, and he notes a tension in Locke’s views between domestic (non-Zero-sum) and international trade (zero-sum). “Locke was a mercantilist in the sense of favoring an excess of exports of consumable commodities over imports of consumable commodities.” Now Mack actually thinks this in “tension” with Locke’s awareness of the gains from voluntary trade.

My own view is that there is no economic tension here because for Locke trade is, as Mack notes, not voluntary but between nations, which are represented by monopolistic/corporative/privileged companies that act in the interest of the elites that run them. (Setting up corporations was not liberalized until the nineteenth century by that keen reader of Smith, Gladstone.) Of course, there is a tension here in Locke’s art of government because the wise prince has to guard against faction—and these monopolistic corporations are, in fact, partial to particular interested. (As Smith would diagnose and say say, they claim to trade in the general interest, but that’s impossible.)

Of course, the reason why Smith calls Locke a ‘mercantilist’ is not limited to Locke’s views on trade. Rather, as I have argued, Locke views having more money than other countries as a strategic asset in economic and military affairs. And that’s because Locke is not just making an empirical argument about international affairs (that he might regret normatively), but rather Locke also thinks this zero-sum nature of international relations is constitutive of it.

And this suggests that Smith may not have been wholly unfair to treat Locke’s view as one involving domestic population growth characterized by voluntary trade, and international land-grabbing (and the managing of these lands) as central to the wise art of government.

*UPDATE: Craig Smith informs me that there exists a 1728 edition of Locke’s Two Treatises that has Adam Smith’s annotations on bits of the first Treatise. It’s on display in Kirkcaldy right now (see here). The 1728 edition is the fifth edition (pretty much the same as the fourth edition mentioned in the text).

"International land grabbing" needs a bit of what the cool kids call "unpacking", I think. IIRC, Locke claimed that conquerors (implicitly, conquerors of white Christian realms) were obliged to respect the property rights of the realms they conquered.

By contrast, for colored people, expropriation and enslavement was always fine with him - a point on which he practised what he preached.