Yesterday, India Smith informed me that George E. Smith (1938-2024) passed away on Friday, November 8.*

I start with a wild story. In the early 1990s, Joseph Almog (then UCLA) gave a talk at Tufts in the philosophy of math. During Q&A he kept calling Jody Azzouni (the resident philosopher of math) ‘George.’ After the talk, the confusion was sorted out. But someone asked, how do you know of George? At that time, George’s stature in the profession was overshadowed not just by Dan Dennett, but also by Hugo Bedau and Norm Daniels. George didn’t publish much. Almog responded to the effect that he had been introduced to George’s work by Saul Kripke at Princeton (in a reading group or seminar, I can’t recall). This came as an enormous shock to George.

Back in the mid 1970s George’s dissertation originated at MIT in a reading group with Richard (‘Dick’) Cartwright on Kripke’s Naming and Necessity. He told me that after he completed the dissertation on quantified modal logic (in 1979, the other committee member was Boolos), he sent a chapter to JPhil and the dissertation to Kripke. JPhil rejected the chapter, and he never heard back from Kripke. This particular combination made George assume that his work on the topic had been not up to par. Years after the Almog visit George told me with some satisfaction that a number of Kripke’s other students subsequently reached out to him when they, in turn, worked on the material.

During the Spring of 1990, at the end of my freshmen year, I first met George on the budget and priorities committee at Tufts. When I joined the committee as a student rep, the committee was charged with offering proposals to eliminate a rather large deficit in the operating budget to Arts & Sciences. (Tufts had a negligible endowment then, so there was little buffer.) George co-chaired that committee (the other co-chair was David Walt, a professor in Chemistry), but because he had a close working relationship with then Executive Vice-President, Steve Manos, George effectively controlled information into the committee and so effectively shaped how we proceeded. He also played tennis regularly with Robert Rotberg, the former provost.

During committee meetings, George himself often told stories from his time in corporate America (including GE) on the functioning of bureaucratic organizations or on how he approached solving the causes of turbine engine failure in extreme circumstances (an oil rig in the arctic or at sea, etc.). Each of these anecdotes was designed to persuade the committee to follow some course of action related to the moral of the story. I learned a lot about engineering, science, and the logic of organizations from these vignettes. He would also tell stories about the early days of the Curricular Software Studio, which he co-founded with Dan Dennett. (Do read Dan’s autobiography on this episode.)

However, while George certainly was not above manipulating us for the greater good, he also created a bunch of research teams to investigate Manos’ proposed budget cuts and to explore alternatives. I was teamed up with David Sloane (who taught Russian lit) and among our ‘topics’ was the possibility to end ‘need blind admission’ and so reduce financial aid. (I quickly learned it wasn’t truly need blind then for all students.) David and I hit it off, and we discovered that there were many administrators who were willing to talk to us and to provide alternative perspectives on the budget.

By the time George and I were both voted onto the board of trustees the following year each of us had our own sources throughout the administration. With a new Dean of A&S, both of us had a lot of opportunities to shape Trustee decision-making. When the interests of faculty and students coincided, we would strategize ahead of time over Indian food on the second floor at one of the malls in Harvard square. (Later our regular standby for ‘work meetings’ became Legal Sea Foods.)

At the end of my sophomore year, I decided George was the smartest person I had ever met; I should try to take a class with him. Because he was an engineer, I looked in the engineering course catalogue. I couldn’t find him; I had two housemates who were engineers, and none of them had ever heard of him. So, eventually I asked him in what department he taught. (This was before the internet.) I was surprised he said, philosophy. In the catalogue, I found his two-semester course on Isaac Newton. I believe it was the third time he taught that course. Years later, I realized George would tell incredibly flattering stories about the questions I asked in that course to later generations of students. (This amused me greatly because I barely managed to pass the course.) At the time about half the enrollment in the course were faculty from other departments, including Drusilla Brown and David Garman (both in economics). I knew Drusilla from the budget committee. The other students were the campus nerds.

Before I signed up, I asked him if that course would teach me what makes a science a science and if it would relate to social science in anyway. (The fall of the Berlin Wall had left me dubious about the scientific nature of International Relations.) In response he said that there was a connection to my interests and added somewhat mysteriously, you will learn how data is turned into high quality evidence. At the time he was helping I.B Cohen to complete the Cohen-Whitman translation of the Principia, and a lot of George’s lecture notes were first published in the Introduction of that volume. (Whitman, who had been a patient of his wife (a nurse), had died a few years before and that was one of the hidden glues of their friendship.)

I heard that phrase — turning data into high quality evidence — many times in subsequent decades (not the least also from Bill Harper and his students at Western Ontario). I have described the experience of what it was like to take that course in other places (here). But see also Kathryn Hume’s memory of his teaching (and other important topics here). George was a phenomenal teacher, who combined enormous demandingness on his students with thorough prep that made his presentations models of clarity and he combined both with infinite patience in giving students extra attention so they could pass the course. George also managed to convey the excitement of research and discovery in class in ways that few other academics manage. Later I was one of the many nominators for various awards accorded to him at Tufts, including The Faculty Research Awards Committee Distinguished Scholar Award and Lillian & Joseph Leibner Award.

He had to miss the Leibner Award’s award ceremony because he was in Chicago for Howard Stein’s fest in 1999. This was a rather impactful visit for George because he met Michael Friedman there for the first time. Friedman was blown away by George’s paper, and he ended up hosting George at Stanford regularly. The paper illustrated Newton’s sensitivity to inferences that are valid even if the antecedent conditions hold only approximately (or quam proxime reasoning).

For me that academic year (1991/1992) changed my attitude to course work. I also took a seminar in political theory with Rob Devigne (on Hobbes) and in English literature with Michael Fixler (on Milton). Fixler had talked me into taking his class based on an editorial I wrote on the budget negotiations for the school newspaper. Junior year, I suddenly was getting a crash course in seventeenth century English thought from three professors who had a mesmerizing, prophetic quality about them. Academia beckoned.

At Tufts I took three classes with George. However, he nudged me away from his course on the analytic-synthetic distinction (in which he taught a manuscript he had co-authored with the late Jerry Katz then at CUNY). At the time, he thought I was not going to be a professional philosopher but an empirical social scientist, and he thought I would find it distracting from my real interests.

In fact, when he had been hired at Tufts, George taught philosophy of social science because his “primary concern was social science, and idealizations in social science.” He had been turned on to the topic by Arrow. Years later, I once asked Alan Nelson (UNC), who became one of my own intellectual interlocuters in early modern philosophy, about his own early great work on philosophy of economics, and much to my surprise I learned that he had been a TA for George at MIT, I believe on his, “methods of computer modeling” in Political Science! Small world.

I passed the philosophy of science course. But I put off writing the three papers for part I of the Newton course. The truth was I wanted to impress him, but also felt totally out of my league. I took an incomplete. I eventually wrote those three papers just before graduation in between many parties. One of these became my ‘writing sample’ for graduate school.

For Part II of the course, at his instigation, I wrote a paper on Boyle’s description of the famous vacuum experiment on the falling feather. I found the work with the description on a microfilm in the Boston public library. It was an ecstatic moment, and I called him from a payphone outside the rare-book collection. George proposed a joint paper. But we later learned from IB Cohen that the experiment was already well described in the literature.

After the Newton course, he enlisted me in a translation from seventeenth century Dutch of some of Huygens’ writings pertaining to gravity and his great debate with Newton. Another person on the project was Karen Bailey. George often collaborated with students on research projects.

In his response to Newton’s argument for universal gravity, Huygens draws on and mentions a report on the use of his pendulum clocks to find longitude at sea that he wrote to the directors of the Dutch East India Company. George wanted me to translate that report for him (and some of the related material) from seventeenth century Dutch. I could barely understand seventeenth century written Dutch, and had no background knowledge in the building of clocks, longitude, and reckoning with maps beyond what I learned in that year long course with George.

In order to create a proper translation with explanatory footnotes, I went to the Leiden University library archives to track down the original of Huygens’ manuscripts and try to trace and check all of Huygens’ references during my Summer holiday. In Leiden I was incredibly lucky to meet the great historian of science Joella (‘Jody’') Yoder. Jody took me under her wings and I got a proper education in archival research and through her I befriended all the key local archivists. Jody was invaluable to my joint research with George. My first publications — on various maps that I rediscovered in the archives — all originated in that work.

George was invited to keynote a conference in Leiden 1995 (two hundred years after Huygens had died), and he proposed we also submit a paper together writing up some of ‘our’ findings. Our key finding was a very big historiographic deal: Huygens’ objections to Newton’s universal gravity were empirical in character. In addition, we discovered evidence (with help from Jody) that Newton and his circle were familiar with the details of Huygens’ empirical objections. Koyré and others (including ‘Tom’ Kuhn, whom I met through George) had maintained the rejection of universal gravity rested solely on Huygens’ dogmatic commitment to the mechanical philosophy.

Now, I would describe myself as a research assistant on the project, but since George had no money to pay me, he gave me credit on our joint papers. Much of that work was written at his engineering gig at (then) Northern Research outside Boston and later also at Dibner. It was an incredible apprenticeship because George was a perfectionist meticulously verifying and recalculating every number in the manuscript. I spent long hours with him dictating our joint paper, and us practicing my Leiden presentation.

Our joint work was the basis of a life-long mentorship and eventually friendship, including a place of honor (next to the rector) at my inaugural lecture as a political scientist in Amsterdam a decade ago. I was so thrilled he flew to Amsterdam for that.

We wrote up a short version of our argument for the 1995 conference, and then, when I was doing my PhD, a longer version for Archive of the History of Exact Sciences. After the paper was accepted, Henk Bos (the editor) asked for modest revisions, including a new appendix. When I realized this was a trigger for George’s perfectionism, I eventually posted the paper at the pitt phil-sci archive (here).

In this period through Jed Buchwald’s efforts, George partially moved to Dibner Institute (then at the MIT), where, after Jed left, George became an acting director and then director for a few years. (You can read his version of the story here, including how controversial his initial appointment was with some historians of science.) He loved their library (which had an astonishing collection also pertaining to Newton), he loved being back at MIT, he loved the location on campus, and he loved facilitating other people’s research. Once when I was looking for a map that Huygens may have used in the library, I realized that it was hanging over one of the study-desks! George was distraught when MIT did not renew its association with the Institute and then, subsequently, the main donor (David Dibner himself an engineer with whom George had a great bond) died. The unraveling of the Institute haunted George for quite a while. I met my later supervisor, Dan Garber, at a Dibner event so for me it has only fond memories.

Before George moved to Dibner he was primarily known in philosophy to people at Tufts and MIT. He was in touch with a few Newton scholars like Curtis Wilson and IB Cohen (whom he greatly admired), and he was in a mutual admiration society with Bill Harper (at Western) and Stein (Chicago). The Dibner appointment made him quite visible to many historians of science. And often he associated his own work with the history of science, even pretending that his work was quite a bit distant from philosophical concerns.

All of this started to change, first, after Steinfest in 1999, then a high-profile exchange with Ernan McMullin in Philosophy of Science (2001) and, then, finally the publication of the Cambridge Companion to Newton that was published in 2002. IB Cohen, who was in faltering health, had asked him to co-edit it. George’s chapter on Newton’s methodology in the Principia made an enormous impact on philosophers’ perception of Newton. (It’s been cited over 250 times.)

In this period, George was invited to write a Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Newton. He convinced Andrew Janiak (who was then a Dibner fellow) and myself to co-author with him. The project became so large we each ended up publishing our own entry (Andew on Newton’s Philosophy; mine on Hume’s Newtonianism and Anti-Newtonianism; and eventually George’s own on Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. For me it was a great lucky break.

When I was a post-doc at WashU (2002-2004), I met Cynthia Schossberger who was then tenure track at SIU-Edwardsville. We started dating. When Dennett caught wind of it, he informed me that she was way out of my league. George, however, told me not to screw up. I asked Cynthia why they were so protective of her. And she told me George had hired her to teach feminist philosophy at Tufts (where she had been a MA student before). George remained an advocate for feminist philosophy in the department.

I moved back to Holland, in part, with a grant from the Dutch Research Council (NWO) to work on the reception of Newton. The inaugural event of my grant, and also my appointment in Leiden, was a four-day conference at “Newton and/as Philosophy” at the Boerhaave Museum with a lot of (then) young scholars. Naturally, George was one of my keynotes. George’s presentation (which became ‘Closing the Loop’) blew everyone out of the water. But for various reasons — not the least of its massive length — it was not included in the subsequent volume with CUP that I co-edited with Andrew (which included George’s “How Newton's Principia changed physics”).

I had been unhappy about the fact that “Closing the Loop” did not fit in that volume, so when Zvi Biener (one of the people I first met at the Leiden event) and I teamed up on another Newton themed conference (at Pitt), I immediately started planning to create a volume that would allow “Closing the Loop” to be published. To Peter Ohlin’s credit at OUP, he allowed himself to be persuaded by me (and his referees) to include it. (He also gained my undying loyalty.) I quote from Katherine Brading’s NDPR review of the volume.

The last and crowning article [of Newton and Empiricism] is Smith's "Closing the Loop: Testing Newtonian Gravity, Then and Now". At over eighty pages, few journals or edited collections could or would have found space for it. It is to the editors' enormous credit that they published this important and rich article in its entirety. Those familiar with the work of Smith and Bill Harper (for Harper, see his 2011) will know that several decades of careful and detailed study of Newton's Principia and the methodology therein are now coming to fruition, and that this work has far-reaching significance in philosophy of science, methodology and epistemology, with respect to both history of philosophy and contemporary work in those areas. Working out the details of these implications is a collective undertaking, and "Closing the Loop" is an invaluable resource. It should be compulsory reading for anyone interested in the relationships between theory and empirical evidence, and in what kind of knowledge can be supported by the interplay between our theories and our experience of the world….

Do read her summary or just take a long weekend to study the article, which is fast becoming a classic.

Others can speak more on the golden years that followed. George became a regular visitor at Stanford and, through Katherine Brading, at Notre Dame. While George was very grateful to Tufts, these opportunities allowed him to share his views with the discipline’s best philosophers of science. (I often joked that I have never been so scared as the time that he drove me around Palo Alto in his souped-up sports car.) Auditing his legendary Newton course became a rite of passage for many younger scholars in early modern philosophy and history of physics. The course was also online, and often George made sure I would get the log in codes so I can keep up-to-date on his amazing lecture notes.

At Stanford and Notre Dame, George found students that were eager and capable to develop his research program and make it their own in distinctive ways. I am thinking, especially, of Teru Miyake (Singapore), Monica Solomon (Bilkent), Qui Lin (Simon Fraser), Craig Fox (MacEwan University), Miguel Ohnesorge (Cambridge), and Dr. Raghav Seth with whom he wrote the excellent Brownian Motion and Molecular Reality: A Study in Theory-Mediated Measurement. (OUP; 2020). Seth is a physician, but himself a former Tufts undergraduate. In philosophy of seismology, Alisa Bokulic (Boston U) also became a very appreciative and sophisticated reader of George’s work. Prestigious lectures and conferences would follow, and whenever I would call George he could not contain his enthusiasm to share his latest findings and collaborations.

While I nearly always cited George as my first authority on Newton, I used George’s work on Newton in two distinct places to advance my own research. First, (see here) I claimed that Adam Smith’s interpretation of Newton partially anticipated George’s. This was a core chapter of my dissertation. Second, I used George’s account to develop a critical interpretation of Milton Friedman’s and Vernon Smith’s distinctive methodologies in economics (see here). The former ended up corresponding with me, while the latter ended up inviting me to be a regular visitor at Chapman.

George’s work also shaped two dissertations at Ghent University: one by Steffen Ducheyne and one by Maarten Van Dyck, and my involvement with their work as an external examiner led to my appointment as a research professor there. So, even leaving aside our joint work on Huygens, my relatively modest use of George’s philosophy of science shaped my intellectual life in all kinds of quite unpredictable ways. Elsewhere, I was, however, rather critical of George’s tendency to treat deviations from his reading of Newton by figures in the past as mistakes/errors (rather than as philosophically motivated).

My association with George also led to an invite to write a handbook article “in the spirit of George” on the Principia for a history of physics handbook edited by Buchwald. Panic stricken, I naturally suggested to ask George. I forgot the way Jed phrased his response, but I realized I was not the only one that worried George’s perfectionism slowed down his rate of publication. I was smart enough to team up with Chris Smeenk (who was naturally first author), and I am immensely proud of our joint effort.

At the event in George’s honor in 2018 at Tufts, On the Question of Evidence, I met innumerably many of George’s students (and, of course, his colleagues). It was immensely gratifying to see the outpouring of love for him. During my long covid, I was too sick to help Chris and Marius Stan to co-edit the fest volume, Theory, Evidence, Data: Themes from George E. Smith, but I was very pleased to help them with the introduction, which aims to convey to other philosophers of science the significance of George’s work. I don’t think I can improve on that here. However, we were conscious of the fact that George had done a similar exercise (with Jed) to convey some of the lasting salience of Kuhn.

I saw George twice more. Once, while I was a visitor at Duke (also, in part, thanks to Brading), I flew up for his joint retirement party with Dan at Tufts. Both of them had called me to tell me that the other would really be pleased if I showed up. As I noted, I didn’t speak publicly because I was afraid that with my long covid head I couldn’t due justice to the occasion. The following day we had a long lunch at Legal Sea Foods near MIT. I learned that ‘retirement from Tufts’ was a relative term. He was already scheduled to teach several courses the next academic year.

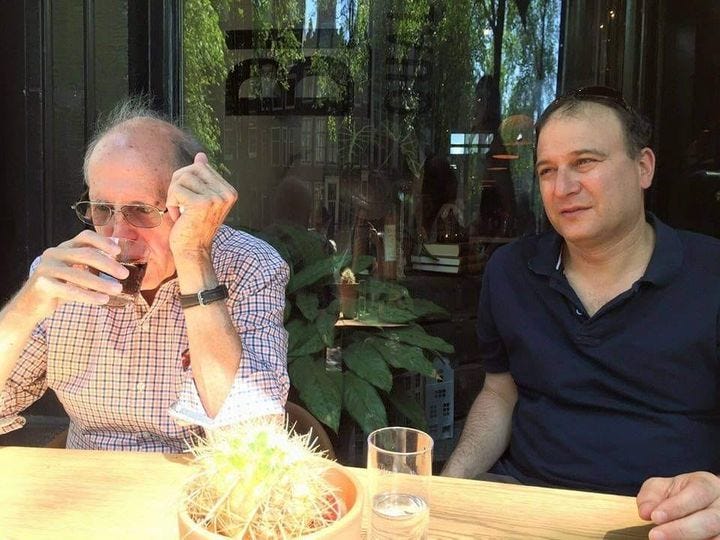

This past Summer, after I learned he had been diagnosed with terminal cancer I made a point to visit him in late August. I knew it was serious because throughout the Summer he wrote me to discuss what to do with his remaining projects. I took the green line out to Newton, and walked up the hill to his home near the Reservoir. He took me, and his wife India, out for lunch at the Legal Sea Foods in Belmont (which has a lovely view over a meadow). India drove. During lunch outside we mostly spoke about the past, but I had the distinct impression he carefully choreographed what he wanted to impart to me.

George was born in Cincinatti (and he liked that this was also true of Thomas Kuhn). He was an undergrad at Yale (philosophy and mathematics), where Fitch was one of his major influences. He also met India in this period. George had not gone to a prep school, and he made money playing poker and also took time off to work at GE, where he first worked with engines, and Pratt Whitney.

He returned to academia in 1964 at Harvard. But dropped out after a year. And started working at a consulting firm in Cambridge that became Northern until 2013. Throughout his life he was interested in civil rights and basketball. A lot of the courses he taught, when unrelated to Newton scholarship or intro to logic (also legendary), were often on issues pertaining to social justice. During our final lunch, we were both beaming with pride when I could talk to him about my son’s rapid improvements as a basketball player.

Chomsky was a huge influence on George’s thinking on turning data into evidence. And he often would mention his association with ‘Noam.’ When George was insecure, he would name-drop. But this was never irritating because the celebrities he cared about were all intellectual and he cared about them for their intellectual insights and what these taught him (not the least Allan Franklin). However, he wouldn’t tell you that while in grad school he co-published a rather famous paper in Behavioral and Brain Sciences with Kosslyn, Pinker, and Schwartz. That I learned from Dan Dennett. (I suspect this helped him get tenure.)

The longue durée, fine-grained study of the confirmation processes behind the production of scientific knowledge is George’s methodological innovation to philosophy of science. George’s work reframed questions about the ‘realism’ of science in terms of the stability of (iterative) evidential reasoning over many centuries. This was a most unlikely response to Kuhn’s arguments.** That George has managed to convince some of the most talented people in history and philosophy of science that his view is even plausible is testament to the richness and rigor of his case studies. Along the way he demolished the idea that Newton had used either straight induction or hypothetico-deductive reasoning.

Back in the Fall of 1990, he took his Newton class students outside to look through a telescope with a magnification that Galileo had used to look at the Moon and the moons of Jupiter. He had enlisted one of his daughters to set it up. It was bitter cold. But none of us dwelled on that because George was so excited on our behalf. I regret to report that I saw only blurry stuff. That blur was, of course, the point of the exercise. Galileo’s discoveries were not a consequence of pure empiricism. What they were was not so easy to say. Later, I paid homage to that evening when I called my bullmastiff, Sagredo.

My condolences go to India and his two daughters. George asked to be cremated and did not want a burial service. May his memory be a blessing.

*As always these posts may be more informative about my perceptions than George.

**Some other time I will share my memory of George introducing me to Kuhn.